How to Become the Technology Writer You Want to Read

The lessons from Wired, Whole Earth Catalog, and the writers who shaped how we think about technology—and a complete playbook for becoming an effective tech writer.

How to Become the Technology Writer You Want to Read

The lessons from Wired, Whole Earth Catalog, and the writers who shaped how we think about technology

I spent years trying to become a better writer by writing more. But I had the equation backward.

The insight came from Kevin Kelly, founding executive editor of Wired Magazine: "I don't have the ideas that I'm going to write down. My ideas come through the process of writing."

Writing isn't transcription. It's discovery. You start not knowing what you think, and you write to find out.

This shifted everything for me. I stopped waiting for ideas and started writing toward them. The page became a thinking tool, not an output device.

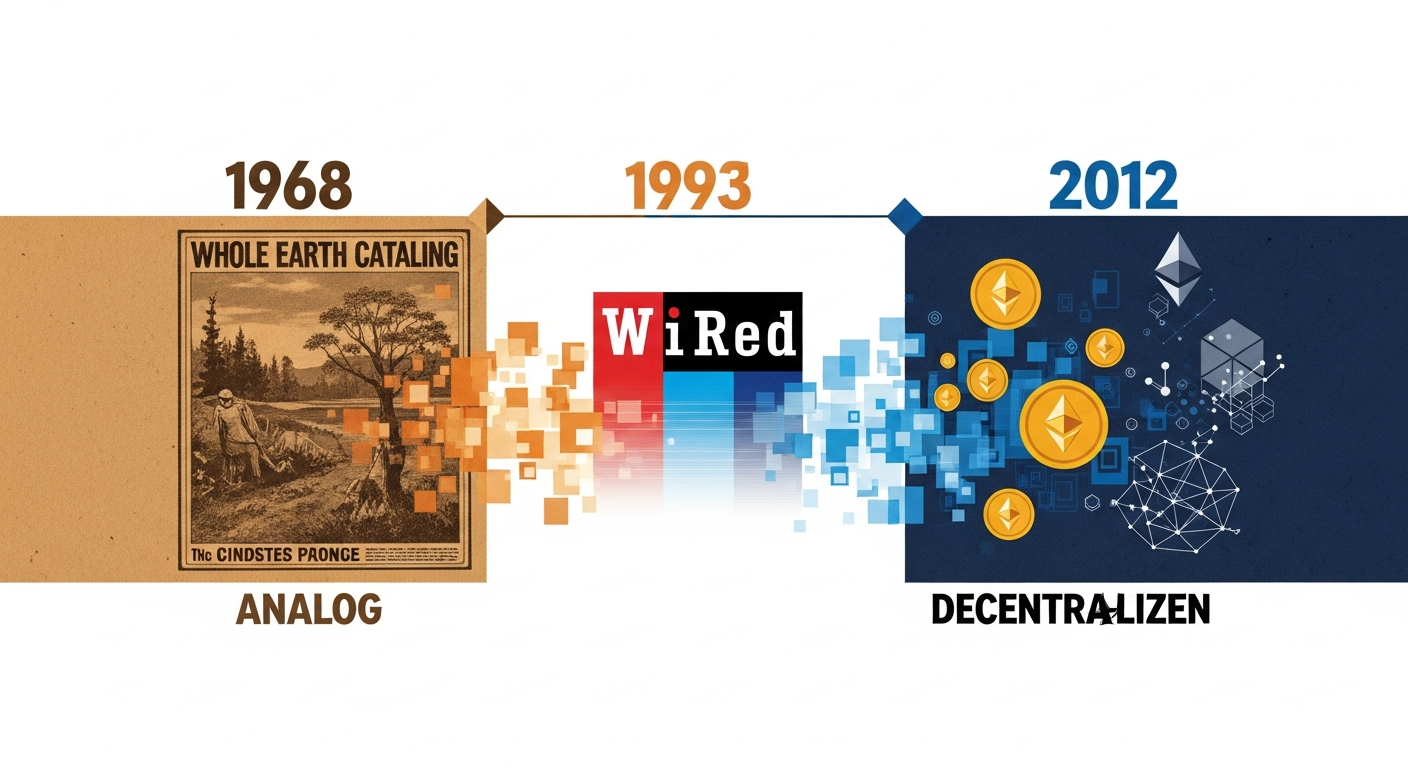

But there's more. After studying the three most impactful technology publications in history—Whole Earth Catalog, Wired Magazine, and Bitcoin Magazine—I found a full playbook for technology writing that goes far beyond "write more."

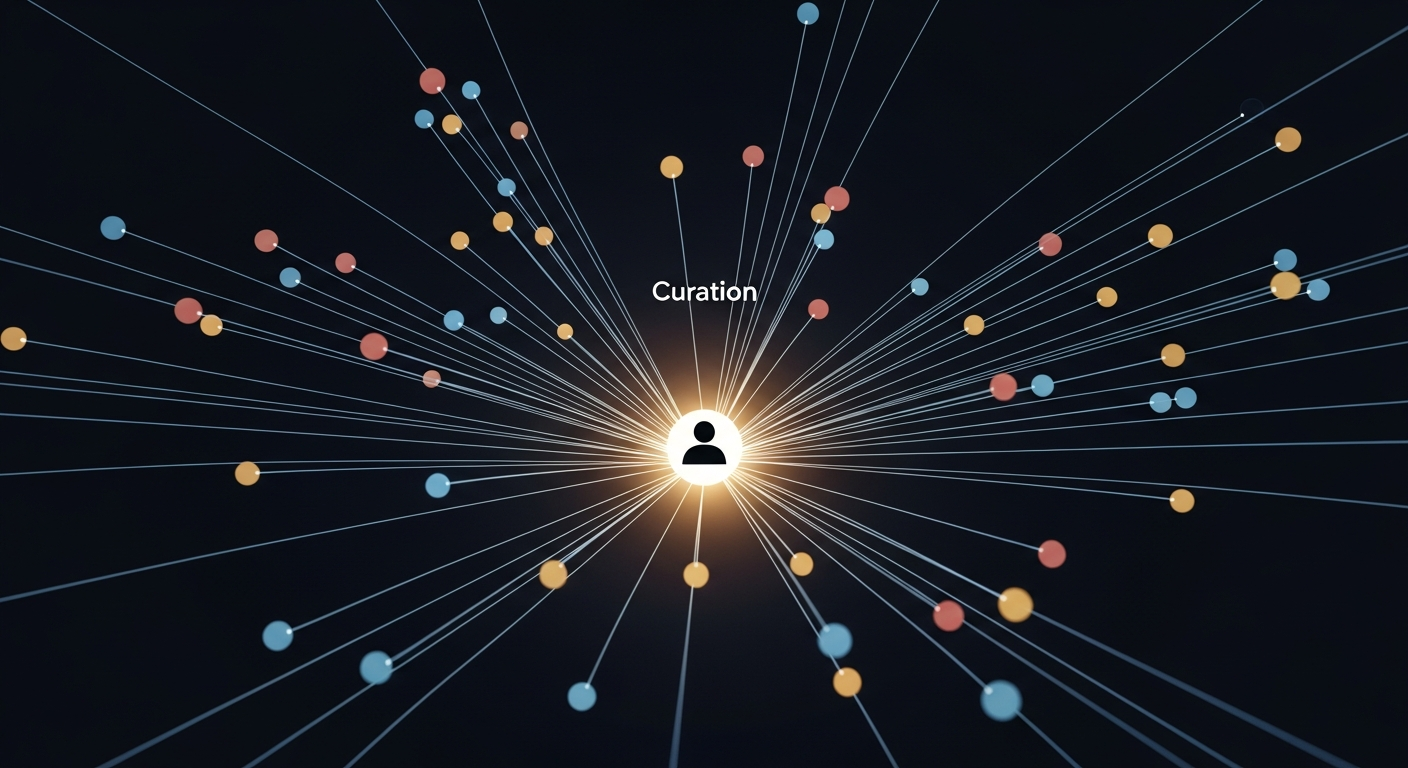

The Curation Principle

Stewart Brand founded the Whole Earth Catalog in 1968. It wasn't a magazine—it was a collection of pointers. Brand's philosophy of "access to tools" meant providing gateways to resources rather than instruction.

His insight on curation still haunts me: "Curating is assembling, letting other people do most of the work. It's a very lazy, therefore good, way to influence the world."

The Catalog's power came from what it pointed to, not what it created. In an era of information scarcity, curation was access. Today, with information abundant, curation is filtering. Different context, same function: helping people find what matters.

Morning Brew built 2.5 million subscribers by curating daily business news. Tim Ferriss's 5 Bullet Friday became one of the largest newsletters through curation alone. They're the Whole Earth Catalogs of our era.

The practical lesson: Start with 80% curated content (with your commentary) and 20% original. You can build influence by pointing at what matters, not just by creating from scratch.

The Feynman Test

Richard Feynman, the Nobel physicist, had a simple test for understanding: explain it to a 12-year-old.

"If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough."

For technology writers, this is the core skill. We translate between worldviews. Engineers think in systems—inputs, processes, outputs. General readers think in stories—characters, conflicts, resolutions. Business readers think in impact—costs, benefits, risks.

The technology writer must inhabit all three minds, catching where a technically accurate statement will mislead a non-technical reader.

The Feynman Technique:

- Pick a concept you want to explain

- Write it out as if teaching a child

- Where you resort to jargon, your understanding is incomplete

- Return to sources, fill gaps, simplify further

Before publishing anything, I now run it through the Feynman test. If I can't explain it simply, I'm not ready to write it.

The Morning Principle

Nearly every successful writer I researched shares one pattern: protected morning writing time before digital input.

Haruki Murakami rises at 4am, writes for 5-6 hours, runs 10 kilometers, and is in bed by 9pm. "The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it's a form of mesmerism."

Paul Shirley writes "in the morning, before I turn on my phone or my computer. This last part being particularly important."

Tolstoy wrote daily "not so much for the success of the work, as in order not to get out of my routine."

This isn't about willpower. It's about cognitive architecture. The morning mind, not yet reactive to email and social media, is closer to the dream-state creativity that produces novel ideas. Once you check inputs, you become reactive. You're processing others' thoughts, not generating your own.

The practical lesson: Write first. Then check email. The sequence matters.

The News Sense Questions

Good technology writers have "news sense"—an intuition for what makes a story. It seems mysterious, but it's trainable.

Five questions will develop yours:

- Is it new? First report wins; old news is no news

- Is it important? Does it affect significant numbers of people?

- Is it interesting? Would your audience care even if not directly affected?

- Who is affected? Specific stakeholders ground abstract stories

- Is there a human element? Stories about people resonate more than stories about things

Ask these questions systematically for every potential story until they become automatic. News sense is instinct, but instinct built through repetition.

The Niche Imperative

Generalist technology coverage is dying. Niche publications are winning.

The logic is simple: readers want depth, not breadth. A publication that covers "AI in healthcare" builds more loyal subscribers than one that covers "technology." The focused publication can go deeper, build community, and become the definitive source.

Nathan Barry's advice: name your newsletter "iOS Design Weekly" not "Design Weekly." The specificity attracts a committed audience rather than casual browsers.

The practical lesson: Pick a niche where you have genuine expertise or passion. Go deep rather than wide. Become the person who knows more about your corner of technology than anyone else.

The Independence Standard

Bitcoin Magazine, co-founded by Vitalik Buterin in 2012, established a standard for editorial independence in an emerging field. Their policy is explicit: stories are accepted "entirely on their journalistic merits." Writers are forbidden from accepting third-party payment for coverage. Corrections are transparent.

This matters because trust is the technology writer's only asset. Once you've accepted payment for coverage—once you've let advertising influence editorial—your words mean nothing. You're marketing, not writing.

The Whole Earth Catalog and Wired followed the same principle. They covered technology they believed in, not technology that paid them.

The practical lesson: Maintain strict separation between editorial and commercial interests. Your credibility is your only real product.

The Playbook

Pulling it all together, here's the daily and weekly practice of effective technology writing:

Daily:

- Write first, in the morning, before checking email

- Read 3-5 high-quality sources (Benedict Evans, Stratechery, MIT Tech Review)

- Save items worth curating to a systematic list

- Ask the five news questions for any potential story

Weekly:

- Publish your curation (consistent day and time)

- Deep-read one long-form piece, studying structure not just content

- Engage with your community (comments, responses, outreach)

- Identify one coverage gap—a story no one is telling

Monthly:

- Write one original deep-dive beyond your curation

- Audit your sources (cut poor performers, add new ones)

- Analyze your best-performing content (why did it work?)

- Network with other writers (seek feedback, pitch collaborations)

The Pattern Across Eras

Every legendary technology publication emerged at the beginning of a technological revolution:

| Publication | Revolution | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Earth Catalog | Counterculture/tools | 1968 |

| Wired | Internet/digital | 1993 |

| Bitcoin Magazine | Cryptocurrency | 2012 |

If the pattern holds, the next legendary publication will emerge from the AI/automation revolution. Someone is building it right now—maybe you.

Start Tomorrow

The technology changes. The principles don't.

Stewart Brand's "access to tools" philosophy from 1968, Kevin Kelly's "writing as thinking" from Wired, and Paul Graham's "bold but true" advice remain as relevant today as when they were articulated.

You don't need permission. You don't need credentials. You need:

- A niche you care about

- Morning writing time

- The discipline to curate and publish consistently

- The Feynman test for everything you write

- Editorial independence from the start

Start tomorrow. Before you check your email.

For the complete playbook including source lists, newsletter recommendations, and workflow tools, see my full research analysis [link].

Written by

Global Builders Club

Global Builders Club